Mrs. Sara B. Schaeffer was born in Galena, Ohio in 1857 but spent most of her life in Minnesota.

She was the widow of Major Charles M. Schaeffer (died 1900) who served in the Spanish American War.

During the Spanish American War, Mrs. Schaeffer accompanied her husband to the battlefield where she was known as “The Mother of the Fourteenth Minnesota Volunteer Infantry” which was the infantry in which her husband commanded a battalion. She headed the emergency nursing station for the Fourteenth Minnesota and was much loved by the soldiers she cared for.

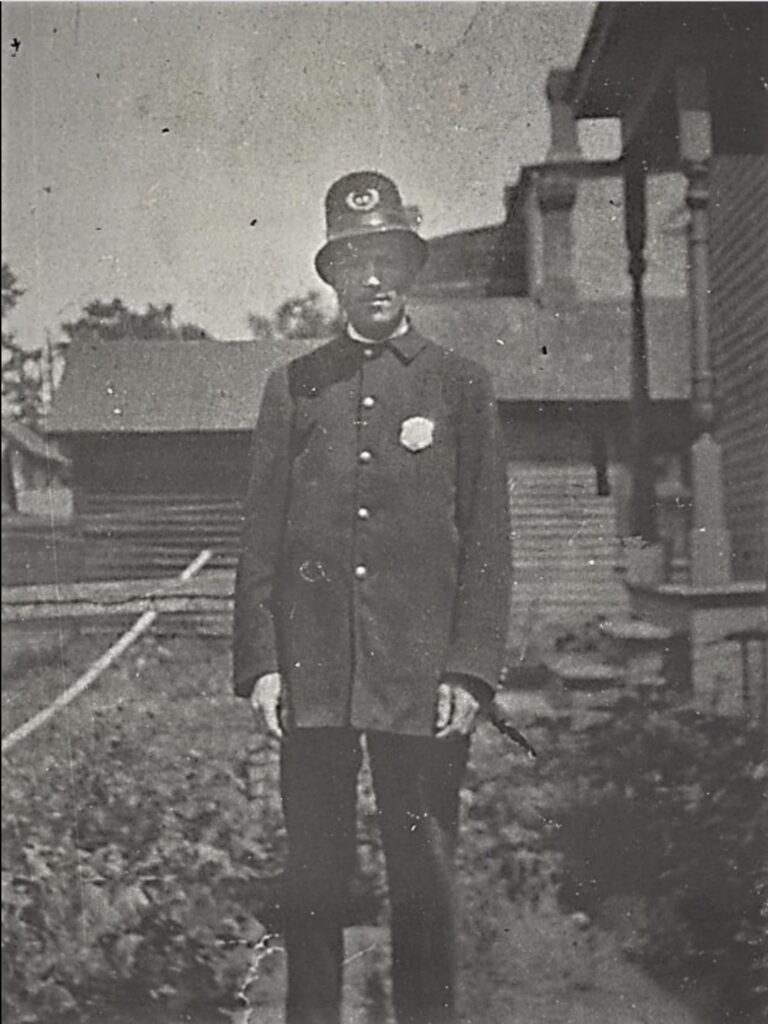

Upon the death of her husband, Mrs. Schaeffer became more deeply involved in church, civic, and women’s organizations where she made many friends. When she became interested in becoming Police Matron, her friends were concerned that she would not have the strength for the work so soon after her husband’s death. She was in a fragile state indeed but the work gave her purpose and as a result she was able to regain her health and sense of well-being.

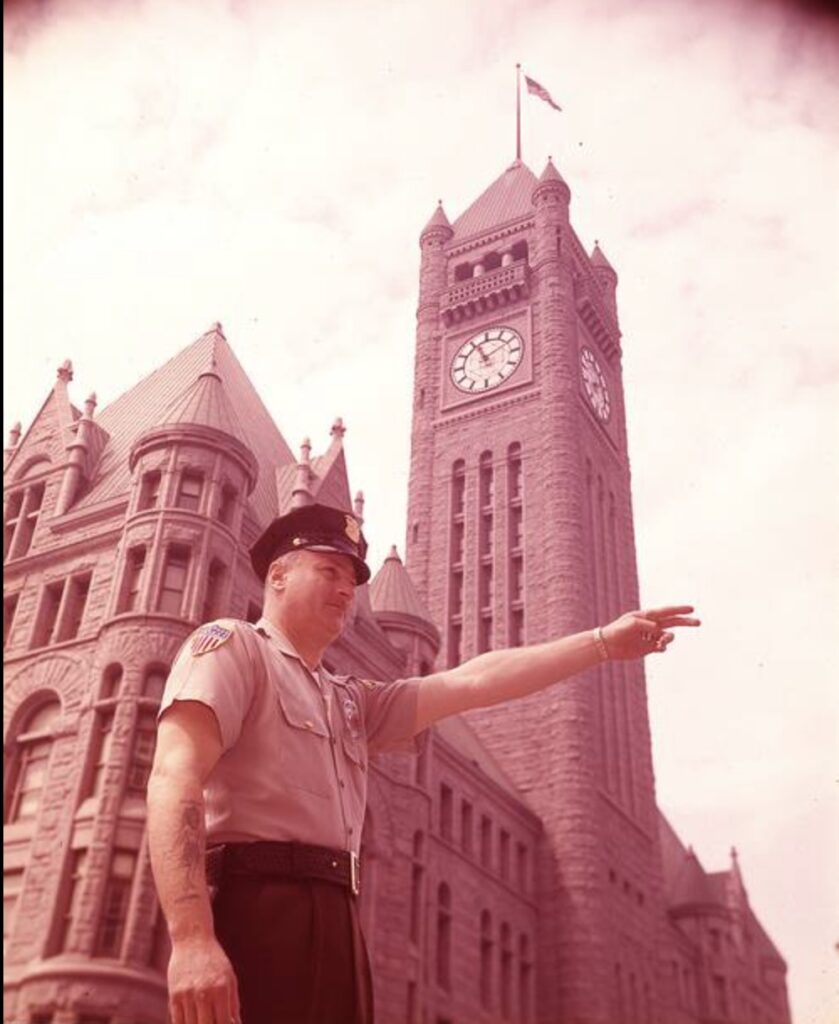

Mrs. Schaeffer was appointed by Mayor A. A. Ames to the role of Minneapolis Police Matron in 1901 at the salary of $726 per year. She served at the City Jail, located on the top floor of the Minneapolis City Hall for 27 years under 11 different police chiefs. She lived in a two-room suite adjacent to the women’s cells for most of that time.

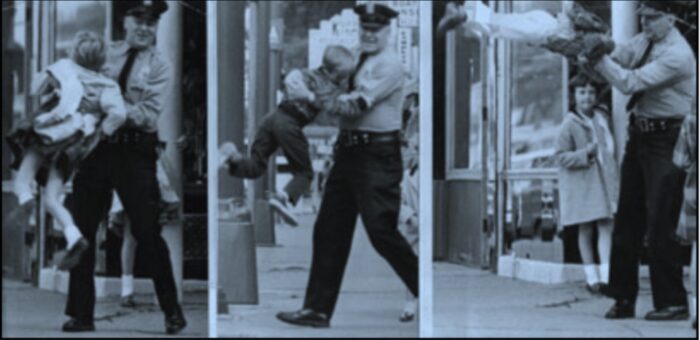

When Mrs. Schaeffer began her service, before the advent of policewomen and before the time of women patrol officers, the Police Matron was responsible for all interactions with women and juveniles from the time they were detained by officers until their release from the City Jail. She also had responsibility for lost and neglected children and abandoned wives.

After 1914, when the Minneapolis Police Department began to hire policewomen, Mrs. Schaeffer was relieved of some of her street responsibilities and was able focus her work on helping women and juveniles during during their time in the City Jail and during their court appearances. It is estimated that by the end of her career she had worked with approximately 100,000 women, boys, and girls.

When Mrs. Schaeffer joined the Minneapolis Police Department, women were taken from the jail to the court in an open wagon for all to see. Mrs. Schaeffer objected to this practice because of the damage it could do to the reputations of women who might subsequently be found to be innocent by the court. She worked with the Department and in quick time was able to change this practice and walk her prisoners to the court instead. Mrs. Schaeffer took pride that no prisoner whom she escorted ever attempted to escape. Her promptings to the Department further led to the purchase of a covered Black Maria for prisoner transport.

Mrs. Schaeffer was known by all as a kind and compassionate woman who was also no pushover. Like many Police Matrons of her day, she was optimistic about the ability of some criminals to reform and realistic about the terrible impact of their crimes upon their victims. If she felt that a woman could successfully re-enter society after her release, she followed up and helped her to find a job. The walls of Mrs. Schaeffer’s suite at the City Jail were covered with the wedding pictures of women she had helped and many of them visited her later to introduce their babies and celebrate other milestones in their lives.

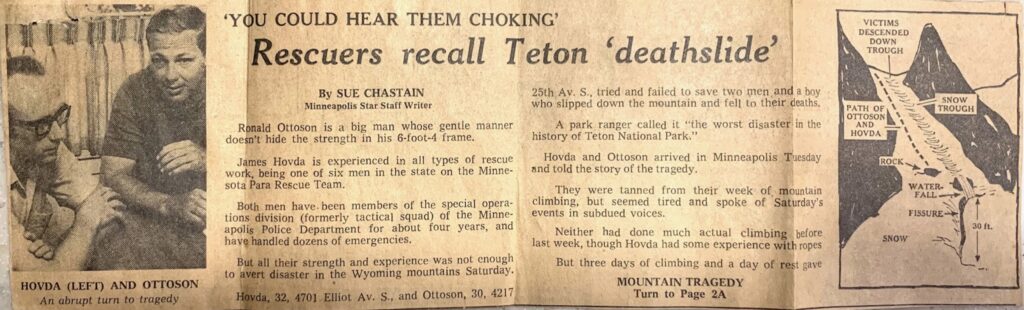

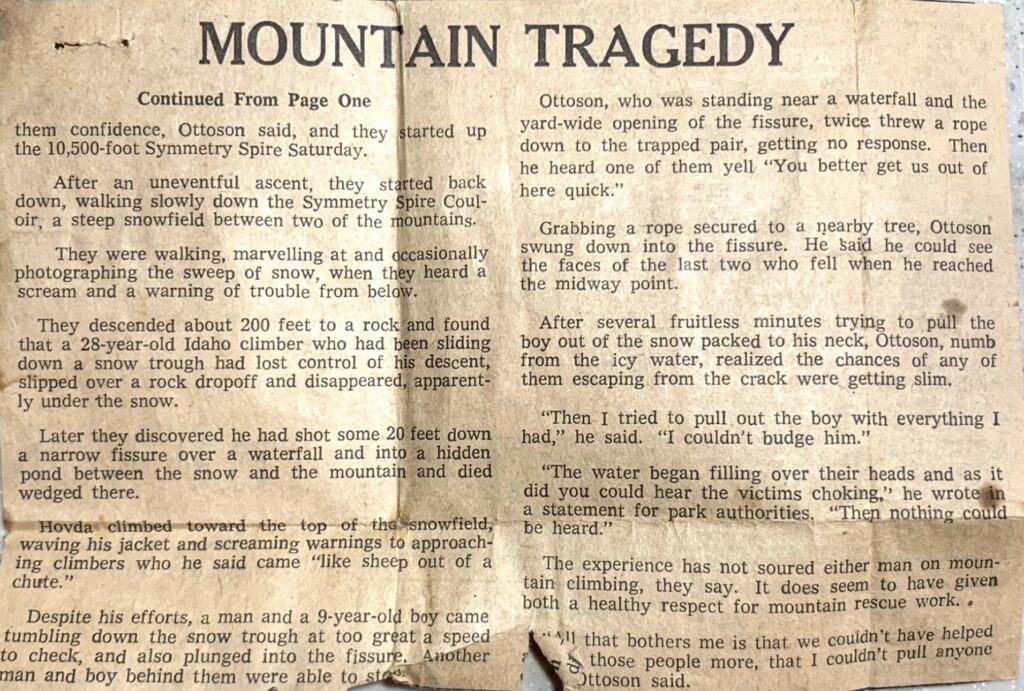

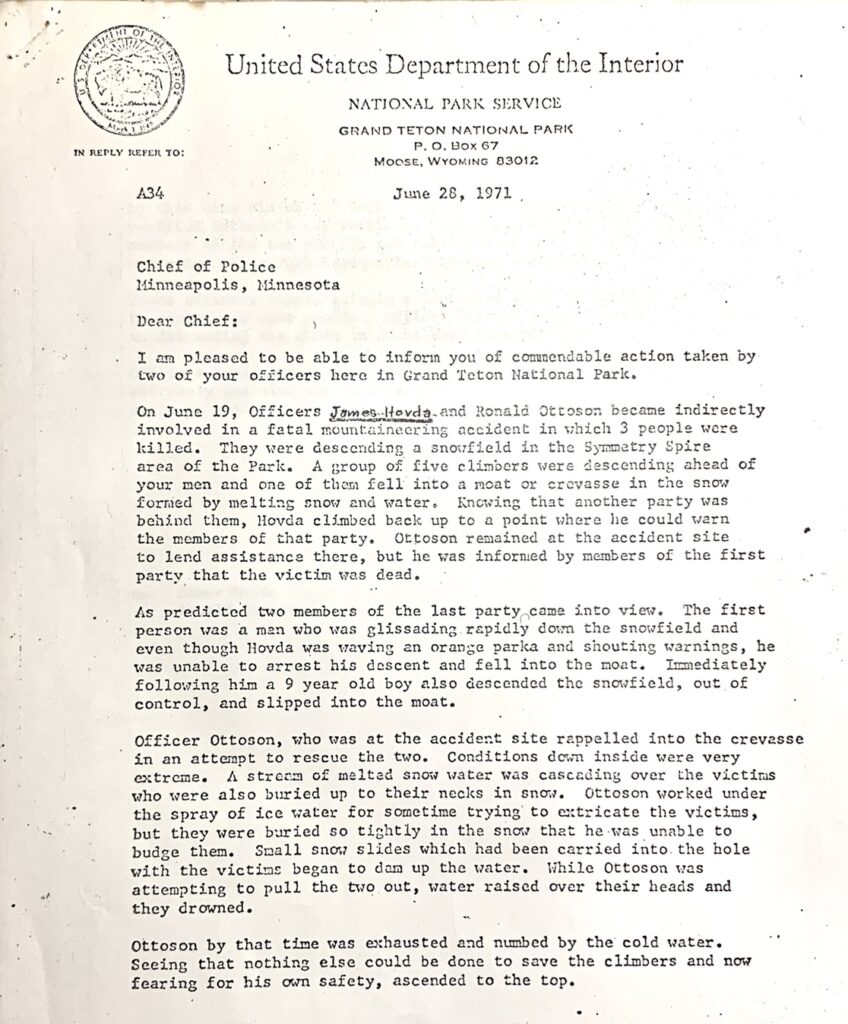

Mrs Schaeffer retired from the Minneapolis Police Department during Mayor Leach’s term, in 1927. She was honored by him and by Police Superintendent Frank Brunskill along with a host of county and federal judges, districts attorney, civic and business leaders and various members of the Minneapolis Police Department at a banquet. On this occasion, Mayor Leach said to her “I want to thank you for the service you have rendered the community and humanity in general”. Detective Thomas P. Gleason recited a poem that he had written in her honor.

A fund of $8000 had been subscribed and invested for her and part of the money was used to purchase what Mrs Schaeffer referred to as her “cottage” where she intended to spend her time tending her flowers.

Sixteen years later, funeral services for Mrs. Schaeffer were held at her beloved home at 3223 Portland Avenue South. She was buried at Lakewood Cemetery on the afternoon of April 16, 1943 with family and friends in attendance.

Mrs. Schaeffer’s cherished home still stands today as the well-restored Bridgham House B&B.