In August of 1939, Minneapolis Chief of Police Frank P. Forestal received a letter from a Mrs. Frank Thissen of Ellendale, Minnesota.

Mrs. Thissen had a problem that she thought Chief Forestal might be able to help to her solve.

She had six small children, all nine years of age and under. They lived on a big farm and she found it nearly impossible to shout loud enough for them to hear that it was time to come in from the fields and meadows where they were playing to do their chores or eat their meals.

They just couldn’t seem to hear her.

Mrs. Thissen had tried using an official basketball whistle to call the children but to no avail.

Then it dawned upon her that a police whistle must be very loud and so she wrote to the Chief to ask if he might be able to send her a discarded police whistle or direct her to a place where she could buy one.

Chief Forestal handed Mrs. Thissen’s letter over to George Gee who was the Police Property Custodian. Mr. Gee searched through the property room and tested out various whistles before settling on a large antique one not used in decades and a slightly-used traffic whistle as being up to the challenge.

The Chief sent the two whistles to Mrs. Thissen with great confidence that they would save her voice and bring her children running in eagerly from their play to do their chores and eat their meals.

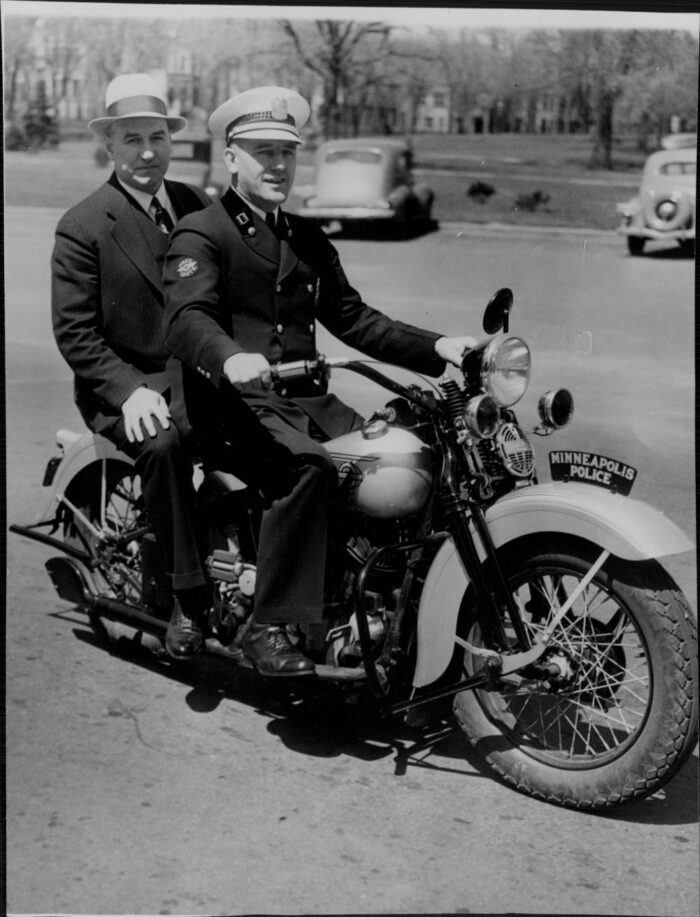

Photograph of Captain Oscar Bakken (right) and Chief of Police Frank P. Forestal (left) trying out a new motorcycle in 1937 courtesy of Hennepin County Library

Story from Minneapolis StarTribune of August 9, 1939