If you are middle-aged or younger you might believe that dialing 9-1-1 in a police, fire, or medical emergency has always been a thing.

But that is not the case.

Before November 31, 1982, if you had an emergency, you would open up your telephone book to find the number for the police, fire or ambulance and then call the appropriate seven-digit number for your particular emergency.

With the advent of 9-1-1, you could call one easy-to-remember number and then the dispatcher would send the appropriate agencies to your rescue.

The move to 9-1-1, as with most changes, had its smooth and rough spots.

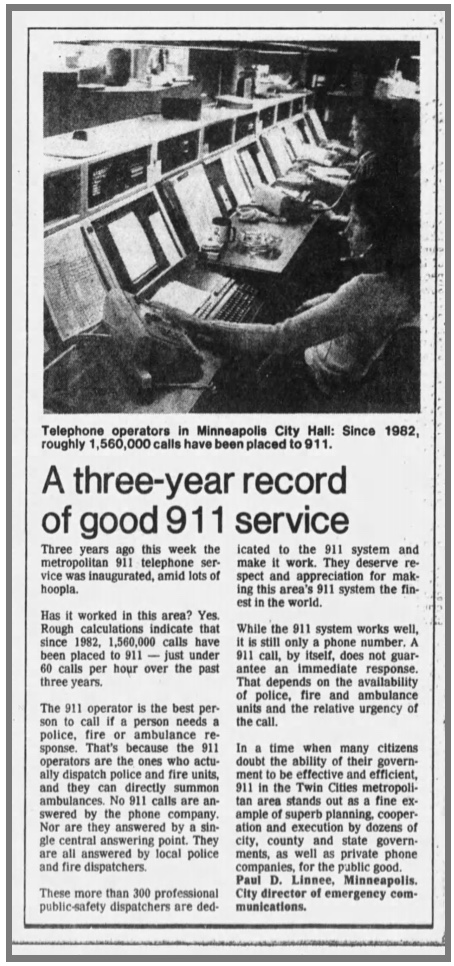

The initial rough spot was the large number of curiosity calls to 9-1-1. This happened because people wanted to verify whether 9-1-1 could actually see their address when they called and because they had various questions about 9-1-1 operations. Large volumes of hang-up calls were also reported in the first weeks of 9-1-1. When asked why they called and hung-up, people responded that they just wanted to make sure that the phone number worked.

The initial education campaign for 9-1-1 indexed heavily on its use for emergencies only. It took a while for people to settle on a practical definition of “emergency” and additional communication was needed to help people understand that they did not need to wait until a crime had actually occurred to call 9-1-1 but that they should call if they suspected that a crime was developing; for example, when an unfamiliar person was peering into the windows of their vacationing neighbor’s house or when someone was walking down the street looking into car windows.

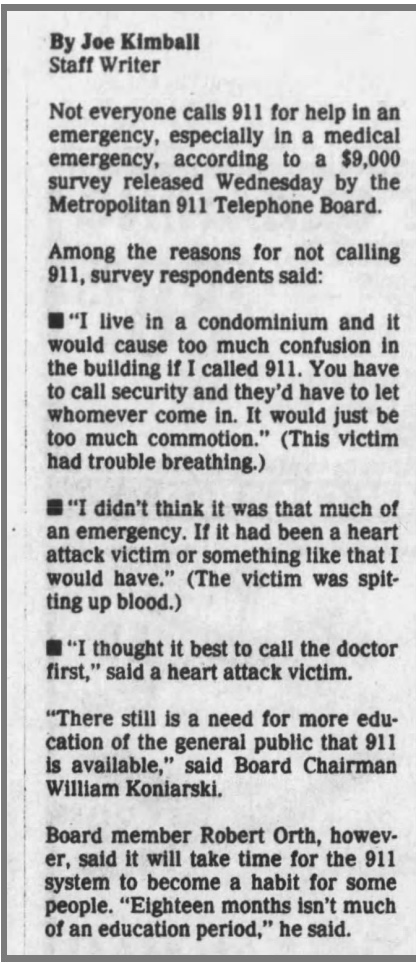

In the first 18 months of its existence, people were especially hesitant to use 9-1-1 for medical emergencies and still generally first called their doctors to discuss their condition before calling 9-1-1. From a Minneapolis StarTribune article of June 28, 1984 we learn the following:

In the summer of 1983, Minneapolis experienced a rash of robberies of elderly couples and rapes of elderly women. It was suspected that one man was committing these crimes. In September of 1983, a 9-1-1 call from an elderly couple who had just been robbed was the key to apprehending the suspect. Third Precinct Captain Dan Graff said that the timing of the police in capturing the suspect within minutes of his latest robber was “extraordinary”. “It’s a credit to the 9-1-1 emergency line, to the officers and to the surveillance effort going on at the time”.

Top advertisement from the Minneapolis StarTribune of December 7, 1982

Quotation of Captain Graff from the Minneapolis Star Tribune of September 10, 1983